The Washington Post has been running a series of articles exposing how the Smithsonian Institution collected hundreds of brains from indigenous peoples as part of an early-20th century effort to promote Darwinian racism. The motivation for the brain collection was to document how some people were supposedly lower on the evolutionary ladder than others.

Many of these brains are still stored in steel vats at a non-public Smithsonian facility in Maryland.

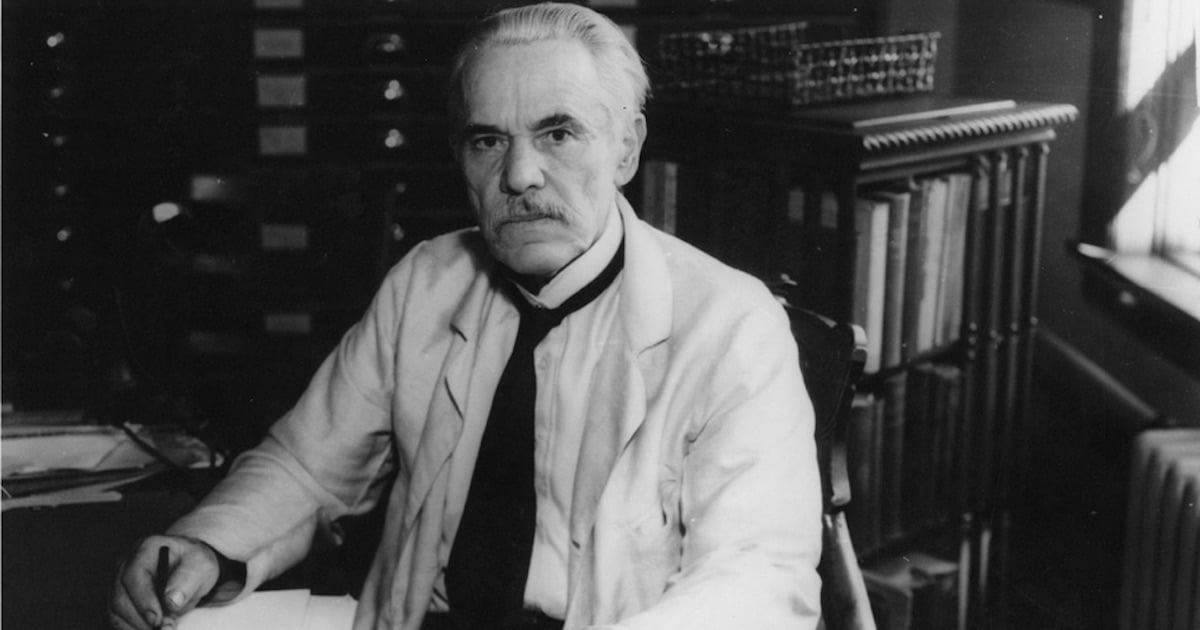

The Smithsonian’s brain collection is finally getting more widespread attention due to the series in the Washington Post series. But the collection — and the man behind it, Aleš Hrdlička — were previously exposed in the 2004 book Ishi’s Brain and by my 2018 award-winning documentary Human Zoos. You can watch the selection about Hrdlicka in my documentary here:

Born in what is today the Czech Republic and trained in the U.S. as a medical doctor, Hrdlička was the Smithsonian’s first curator of physical anthropology, and he was one of the leading proponents of evolutionary racism in the early 1900s. Under Dr. Hrdlička’s leadership, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History became arguably the world’s largest scientific repository of human remains — in fact, at one time, the remains of over 30,000 humans were stored there. Many of the remains were stolen from native peoples without their permission.

Lower on Darwin’s Ladder

These human specimens were collected in large part to dramatize how non-white peoples were supposedly lower on the evolutionary ladder than whites. Dr. Hrdlička scoured the globe for body parts. In 1931, for example, he visited one Alaskan village where he dug up skeletons through the ice and then shipped them back in boxes to the Smithsonian. But Hrdlička didn’t just stop at bones. He wanted what today is called a “wet” collection — soft tissue specimens, especially human brains. Again, his purpose was to show that some races were more highly evolved than others.

Hrdlička collected hundreds of brains, which he embalmed in jars. My documentary Human Zoos tells how Hrdlička went to the St. Louis World’s Fair, hunting the bodies and brains of the indigenous peoples on display there. If they became sick and died, he wanted to be there to harvest their brains to send back for his collection at the Smithsonian. It’s about time that this tragic chapter in the history of Social Darwinism is getting more attention.