Note: This is one of a series of posts adapted from my new book, Darwin Day in America. You can find other posts in the series here.

Note: This is one of a series of posts adapted from my new book, Darwin Day in America. You can find other posts in the series here.

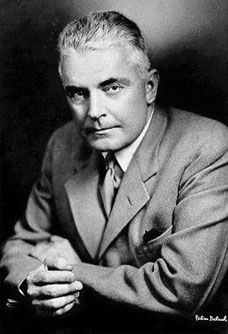

John B. Watson, founder of the behavioral school of psychology, believed that human beings were on par with animals, and so he insisted that they should be studied just like animals. Indeed, he defined behaviorism as “an attempt to do one thing—to apply to the experimental study of man the same kind of procedure and the same language of description that many research men had found useful for so many years in the study of animals lower than man.” He compared opposition to behaviorism to the “resistance that appeared when Darwin’s ‘Origin of species’ was first published.” In his view, the root of the resistance to Darwin and behaviorism was the same: “Human beings do not want to class themselves with other animals.” Watson attributed the rejection of behaviorism by some psychologists to their unwillingness to accept “the raw fact” that “to remain scientific” they “must describe the behavior of man in no other terms than those [they]… would use in describing the behavior of the ox [they]… slaughter.”

Watson was completely serious when he said that the same experimental methods that were applied to animals should be applied to humans, and accordingly he conducted a series of hideous behavioral experiments on human infants that today would probably be rightly regarded as child abuse. Seeking to identify the source of the “fear response” in children, he would place an infant in a bare room, “the walls of which were painted black,” then let loose a cat or another animal to see if the infant would panic. He also would make sudden loud noises near babies and drop them and jerk blankets out from under them. Loud noises, Watson reported clinically, could provoke “crying, falling down, crawling, walking or running away.” Watson also tried to generate a “rage” response by holding the babies’ heads “lightly between the hands,” pressing their arms “to the sides,” and holding their baby’s “legs… tightly together.” He further tried to spark what he called a “love” response in babies by stroking their “nipples… lips and… sex organs.”

Watson was completely serious when he said that the same experimental methods that were applied to animals should be applied to humans, and accordingly he conducted a series of hideous behavioral experiments on human infants that today would probably be rightly regarded as child abuse. Seeking to identify the source of the “fear response” in children, he would place an infant in a bare room, “the walls of which were painted black,” then let loose a cat or another animal to see if the infant would panic. He also would make sudden loud noises near babies and drop them and jerk blankets out from under them. Loud noises, Watson reported clinically, could provoke “crying, falling down, crawling, walking or running away.” Watson also tried to generate a “rage” response by holding the babies’ heads “lightly between the hands,” pressing their arms “to the sides,” and holding their baby’s “legs… tightly together.” He further tried to spark what he called a “love” response in babies by stroking their “nipples… lips and… sex organs.”

Although Watson is widely remembered today for his role in founding behaviorism, what is less well known is his influence on the advertising industry. After leaving his wife for a graduate student, he found himself dismissed from his academic job at Johns Hopkins University, and he subsequently joined the J. Walter Thompson Company, one of the nation’s leading advertising agencies, where he became a proponent of applying behavioral psychology to advertising. The story of his influence on the development of modern advertising can be found in chapter 8 of Darwin Day in America (“The Science of Business”).

To order Darwin Day in America click here. To find out more information about the book (and watch the trailer), visit the book’s website here.